Literature

During the Spanish conquest and colonial times, the new rulers were accompanied by chroniclers who described the country, the people and political events, for example. Luis de Miranda (“Romance”, 1541–45) and Pero Hernández (“Comentarios”, 1554). The liberation from Spain in the early 19th century brought about a national literary flourishing. The authors were influenced by European tradition, but in Argentina less by Spanish role models than in other Latin American states. Above all, it was Mérimée, Dumas, Michelet and Taine who inspired.

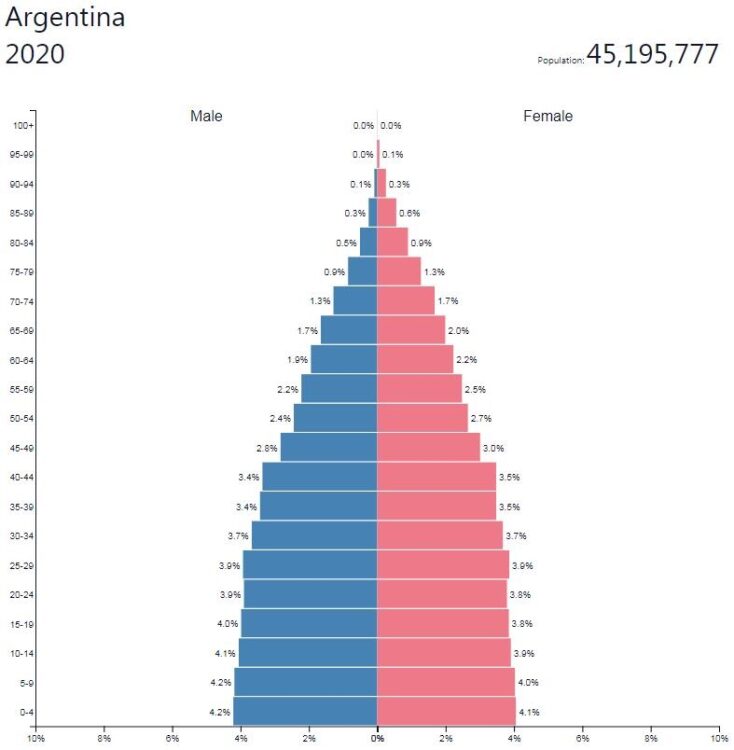

- Countryaah: Population and demographics of Argentina, including population pyramid, density map, projection, data, and distribution.

Literature was part of a civilization process during the 19th century. It also created a linguistic identity, distinct from the European Spanish. In 1838, an association of writers with branches across the country was formed, unique to Argentina through its combined political and literary influence. The authors wrote the nation’s constitution and were MPs and ministers, and two of them – Bartolomé Miter and Domingo Faustino Sarmiento – became presidents. In the essay “Facundo” (1845) with the subtitle “Civilization and barbarism” Sarmiento formulated his thoughts on an Argentine being, where it was to spread education and culture across the vast plains through an expanded educational system.

The ridden gauchon became a symbol of freedom and forward thinking, often portrayed in verse and prose. He received his final elevation to national legend and myth through José Hernández’s verse “Martín Fierro” (1872, 1879), a tribute to the robust, untamed and vigorous. A modern classic in the extensive Gaucho literature is Ricardo Güiralde’s novel “Don Segundo Sombra” (1926).

At the turn of the century, through Spanish-American modernism came a more refined and elegant literature. Its main representatives were Leopoldo Lugones in poetry and Enrique Larreta in prose. Through his original mix of imagination, humor, cosmic perspectives and suggestive word art, Macedonio Fernández influenced the internationally highly acclaimed Jorge Luis Borges, Adolfo Bioy Casares and the circle of the literary magazine Sur, founded in 1931 by Victoria Ocampo. During the 1900’s, Roberto Arlt, Ezequiel Martínez Estrada, Eduardo Mallea and Ernesto Sábato from different points of view and through various means examined the overgrown capital of Buenos Aires and the peculiar Argentine nation.

The slightly later Julio Cortázar shared Borges masterful ability to see and develop the fantastic in existence. Although he lived most of his adult life in Paris, he was a very Argentine writer. Through his passion for experimentation, manifested in a variety of genres, his humor and his open and experimental desire for language and literature, Cortázar became a forerunner of the Argentine literature of recent decades, with authors such as Manuel Puig, Osvaldo Soriano, Antonio di Bendetto, Daniel Moyano, Abel Posse, Marta Traba, Mario Szichman, Juan José Saer, Sara Gallardo and Juan Gelman.

During the military dictatorship 1976–83, many writers were forced into exile. Haroldo Conti, novelist and journalist, linked to the cultural magazine Crisis, never had to leave the country. He became one of tens of thousands of Argentines who were kidnapped and “disappeared”, tortured and murdered by the military. Since 1983, most writers have returned to Argentina.

Argentine literature has over the years remained more European oriented than the literature in other Latin America. However, this has begun to change, paradoxically at the same time as the new Argentinian literature is increasingly gaining in terms of style and composition from abroad.

Drama and theater

In the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, the popular gaucho dramas were very popular, with writers such as Eduardo Gutiérrez and Roberto Payró. Famous Italian and French theater companies touring Argentina with actors such as Eleonora Duse, Lucien Guitry and Sarah Bernhardt became of great importance for the emergence of a national theater. Pirandello’s work was a particularly great source of inspiration. Samuel Eichelbaum, Conrado Nalé Roxlo and Alberto Vacarezza were leading dramatists at the turn of the century. In 1930 Leónidas founded the Barletta Teatro del Pueblo (‘People’s Theater’), in 1935 came the Comedia Nacional Argentina and the 1944 Teatro Municipal in Buenos Aires.

Argentina has had a lively theater since the mid-20th century, which, however, often worked under economic and political difficulties. Among recent dramas, Osvaldo Dragún, Andrés Lizárraga, Griselda Gambaro and Roberto Cossa are mentioned. They have often dealt with burning current topics, sometimes in historical disguise.

Film

Film production in Argentina can be traced back to 1896, when Federico Figner produced at least three films recorded in Buenos Aires. The following year, French immigrant Eugène Py (1859–1924) recorded the literally flag-waving “La Bandera Argentina,” and he continued with his camera from Gaumont to make documentary journal films for the next decade. The feature film production began in 1908 with the Italian-beloved Mario Gallos (1878–1945) “El fusilamiento de Dorrego”. All of these pioneering works have been lost.

During the 1910’s, a permanent film production was established with successes such as Enrique García Vellosos (1881-1938) “Amalia” (1914), the country’s first feature film, followed by Eduardo Martinez de la Paras “Nobleza gaucha” (1915). Among leading directors during the 1920’s were José A. Ferreyra (1889-1943), who wrote screenplays for most of his more than 40 films, including “Palomas rubias” (1920) and “Perdón, viejita” (1927). Julio Irigoyen (1894-1967) also began his career with tango films such as “Alma en pena” (1928), followed by, among other things. “Academia El Tango Argentino” (1942).

The 1930’s and 1940’s became an expansion phase with an average of 42 films per year – many in the country’s special tango and gaucho genres. Argentina then became South America’s leading film producer. Internationally, he got his biggest star in tango singer Carlos Gardel. He made his debut in “Flor del Durazno” in 1917, but came into his own only after the breakthrough of the audio film in the country in 1930. Until his death in 1935 he played in a number of musicals such as “Nights in Buenos Aires” (1931) and “Tango Bar” (1935).

The period 1943–83 during Peronism alternating with military regimes was characterized by totalitarianism and economic instability. Under the pressure of the Catholic Church, the fascist-inspired Juan Perón and the military dictatorships, film production was hampered by political and moral censorship, but also by the US film’s growing market share. Luis Saslavsky (1903–95) dominates the dominant name of the 1940’s and 1950’s, with films such as “History of the una noche” (1941) and “La dama duende” (1945), and Hugo del Carril (really Hugo Fontana, 1912 –89), with successes such as “Las aguas bajan turbias” (1952).

However, towards the end of the 1950’s, Argentina received a new wave of young directors who, with form experiments and social criticism, won international success mainly at film festivals. Most famous became Swedish- chained Leopoldo Torre Nilsson for, among other things. “The Hand in the Trap” (1961). Towards the end of the 1960’s, the younger film-worker generation was radicalized and formed left-wing political colleagues such as Grupo Cine Liberación, in which the world-renowned documentary “The Smelting Furnace Hour” (1967) was co-directed by director Fernando Solanas.

In the years 1975-80, stricter political censorship was applied, limiting production to light comedies and melodramas. With the return of democracy in 1983 came a series of films about the so-called dirty war of the 1970’s, when thousands of political dissidents were tortured and murdered by the junta. Most famously, Luis Puenzo’s (born 1946) Oscar-winning “Children of the Disappeared” (1985) is thought to be. But also Fernando Solana’s “Tango – Gardel’s exile” (1985) and “Return to the South” (1988) relate to the subject.

From 1990 onwards, production increased significantly to reach a peak of 66 films in 2004. Many dealt with subjects such as social injustice, homelessness and crime, but also old sins of the military junta, such as in Israel Adrián Caetanos (born 1969) “Buenos Aires 1977” (2006). Other names with world renown include Carlos Sorín (born 1944; ”Historias minimas, 2002), María Luisa Bemberg (1922–95;“ Camila ”, 1984), Alejandro Agresti (born 1961;“ Valentín ”, 2002) and Juan José Campanella (born 1959; “The Secret in Their Eyes”, 2009).

Art

In line with social and cultural developments, art production among the pre-Columbian peoples of northeastern Argentina reached high levels. Representative are the ceramics and stone sculptures of the Condorhuas culture from the beginning of our era, as well as the figurative of the Aguada culture, at one time human and animal-shaped vessels and tobacco pipes. The Quevedos plate in the Museo de la Plata exemplifies a unique production of sculpted copper plates in large format.

During the colonial era, the mission’s need for images and decorations for its buildings in northeastern Argentina led to a production where Native American and Spanish artists worked together. Prilidiano Pueyrredón (1823–73), portraitist and landscape painter is considered a pioneer in postcolonial art. The Argentine Academy of Art was founded with José Guth (probably of Swedish origin), who arrived in Buenos Aires in 1817, as the first teacher. Impressionism was introduced at the end of the century by Martín Malharro.

Ernesto de la Córcova, a painter with a socialist tendency, initiated the first organized artist association, Nexus, founded in 1906. The Nexus group was followed in 1924 by the Martín Fierro group, which consisted of avant-garde artists and writers, among others. cubist and futurist Emilio Pettoruti. The 1930’s meant a balance when Lino Enea Spilimbergo’s synthesis of the classic and modern was a dominant feature.

In the 1960’s, an experimental art with an attachment was developed in the Torcuato di Tella Institute by artists such as Rómulo Macció and Antonio Seguí and in Marta Minujin’s happenings. In the 1970’s, a neofigurative art movement dominated; some of its more well-known representatives, such as Joaquín Exequiel Linares, Ricardo Carpani and Carlos Alonso, were forced into exile during the military dictatorship. The neofigurative painting was practiced in the 1980’s, especially by groups such as Adev in Córdoba and Grupo Norte in Tucumán.

Architecture

Argentina’s vast and sparsely populated territory determined the different modes of construction before the colonial era. Different types of settlement were adapted to materials and climate. In the 16th century, the Spanish colonization began, which, however, did not reach very far into the country. Buenos Aires became a port for, among other things. Bolivia’s silver exports to Europe. Along the road between Potosí in Bolivia and the estuary of Rio de la Plata, a number of small towns grew up with strong Spanish influence. In parallel, Argentina’s large goods system was developed. Huge haciendas flourished on pampas. The buildings – both residential property of the large landlords and workers’ housing – are Spanish inspired and characterized by simplicity.

The great European immigration, mainly from Italy after independence in 1810, changed the country’s architecture. They began to strive to become part of the western world. Art and architecture were strongly influenced by English. But over time, Buenos Aires’s city plan got a French character with its étoile (circular square from which streets go in different directions) and its avenues. Between the world wars, the architects sought to introduce modernism.

Clorindo Testa, already noted for his office building for the London Bank in Buenos Aires in the 1960’s, together with Sánchez Gómez Manteola and others. a group of architects who are trying to create a regional way of expression with a strong postmodern feel. Architect Miguel Angel Roca, the foremost representative of postmodernism in Argentina, is responsible for the much-debated transformation of the old city center of Córdoba.

Music

Classical music and folk music

As in other Latin American countries, European music and its instruments were introduced through missionary work, especially by the Jesuits. The first organ was built in 1585 in Santiago del Estero. In the 1600’s, music schools were set up, which taught Native Americans and black slaves. The foremost musician of the colonial era was the Italian organist and composer Domenico Zipoli (1688–1726).

When Buenos Aires was appointed the capital of the Spanish Viceroy in 1776, the emphasis of culture was moved there. The opera and cathedral thus became centers of Spanish and Italian music impulses, which were intensified by the extensive immigration, mainly from Italy.

Professional musicians gradually replaced the amateurs, especially since conservatories were founded in the 1880’s. In the early 1900’s, a nationalist composer movement was crystallized alongside traditional cosmopolitanism. Thus, Felipe Boero (1884–1958) composed several operas with native motifs; best known is “El Matrero”, which was premiered in 1929 at the 1908 inaugurated Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires.

After the military coup in 1930, nationalism was subdued. The most prominent and controversial figure of the era was Juan Carlos Paz (1901-72), who meant more as a teacher than as a composer. In 1929-36 he founded and led El Grupo Renovación, which he left when its members opposed the introduction of atonal music. In the circle around Paz, among others, was the artistic adviser to Renovación, Mauricio Kagel and Michael Gielen (born 1927), who both made a career in Europe, Mario Davidovsky (born 1934), who later moved to the United States, and Carlos Roqué Alsina (born 1941)), who built an electron music studio in Buenos Aires together with Francisco Kröpfl (born 1931).

The 1960’s were characterized by the experimental spirit of the time and international contacts. Most prominent was the composer Alberto Ginastera.

The economic stagnation in conjunction with the military junta’s actions against the intellectuals caused a cultural disaster. Talented composers from the 1960’s generation who Antonio Tauriello (1931–2011) and Alcides Lanza (born 1929) left the country. Nevertheless, a development towards a decentralized music life began with music institutions and composer groups in Rosario, Córdoba, San Miguel de Tucumán, La Plata, Mendoza, Santa Fé and – in the 1980’s – in Patagonia.

Among contemporary prominent composers include Osvaldo Golijov and among musicians pianist Martha Argerich as well as conductor and pianist Daniel Barenboim.

Folk music began to be documented on the phonograph as early as 1905. It exhibits a variety of regional characteristics. The almost extinct Native American population of Eldslandet cultivated an emphatic vocal style associated with magic, reminiscent of the folk music of the Northern Hemisphere nomadic people, even though the Sami’s yoke. At the border with Bolivia there is an ink-type mixed music, while the Creole folk music is of European origin.

Carnivals have been of great importance as melting pots for otherwise incompatible cultures. For a few days under anarchist condition, the white upper class was confronted by the black slaves, and various immigrant cultures were enriched by Native American culture. The typical carnival repertoire includes songs and dances such as vidalita, chacarera, zamba and gato.

Tangon occupies a special position between folk music and art music and between dance and vocal music. Originally taking shape in 19th century Buenos Aires, the Argentine tango spread throughout the world and became a cosmopolitan popular music genre of the same musical and cultural significance as North American blues and jazz.

Popular

Singer Carlos Gardel was the big name in the classical era of the tango in the 1920’s-1940’s, when tango moved out of the brothels and became a room-clean popular genre. Tango’s modern history is based on the bandoneonist and composer Astor Piazzolla who, in the 1950’s, incorporated features from art music and jazz into his nuevo tango, giving the genre a completely new status and place on the concert stages.

During the 1960’s and 1970’s, Argentina, like other countries, experienced a musical wave. Vispoet and guitarist Atahualpa Yupanqui (1908–92) and singer Mercedes Sosa (1935–2009) contributed during this time to the development of nueva canción.

A domestic, mainly progressive rock style, rock nacional, emerged simultaneously, with Luis Alberto Spinetta (1950–2012), leader of the Almendra group, and Charly García (born 1951), founder of Serú Girán, among others, as leading music profiles. During the war with Britain in 1982, English-language songs were banned, which accelerated the international breakthrough of the Argentine rock. These musicians, like Gustavo Cerati (1959–2014) with the group Soda Stereo, became very influential for the development of the whole Spanish-language rock. Other popular rock musicians include singer / songwriter Fito Páez (born 1963) and the band Los Fabulosos Cadillacs (formed 1985).

Electronic music has grown in popularity since the 1990’s and has influenced music life in general. In connection with the economic crisis around the turn of the millennium, a domestic, suburban variant of cumbia, cumbia villera, was developed, with a raw, urban expression, partly based on electronic music; today one of the most popular styles among young people. Neotango, is an innovative style where groups like Gotan Project (1999) and Bajofondo (formed in 2002) mix tango with electronic music and other modern features.

The Argentine Jazz was initially thwarted by conservative forces and to some extent has come under the shadow of tango. During the military dictatorship of the 1970’s, jazz was also banned as being “imported”. Thus, many Argentine jazz musicians have made careers abroad, such as swing guitarist Oscar Alemán (1909–80) and tenor saxophonist and composer Gato Barbieri (born 1932). Piazzolla’s nuevo tango gave the indigenous jazz a vital force and has inspired many to jazz fusion, for example the bandoneonist Rodolfo Mederos (born 1940).

The film music composers Lalo Schifrin (born 1932) and Gustavo Santaolalla (born 1951) have created the highest genre of cross-genre music.

Dance

Highly associated with Argentina is the dance and music style tango, which originated in Buenos Aires in the 19th century (see also the section Music above).

Classical ballet was introduced in Buenos Aires by French and Italian guest artists as early as the 1820’s. Since Teatro Colón was inaugurated in 1857, the audience got to see most of the European repertoire. The new Teatro Colón was opened in 1908 and then got its own permanent dance ensemble, but the guest stars surpassed all the indigenous people.

In 1968, Buenos Aires received a new, more modern ballet at the Teatro San Martín, and from it originated Oscar Araiz, a choreographer who is also known abroad. A big name in his home country and internationally was Iris Scaccheri, a modern dancer and choreographer who in Sweden starred in Suzanne Osten’s films “Mom” (1982) and “Lifelike film” (1988). Argentine dancers with international fame are Jorge Donn and Julio Bocca and Eugenia Parrilla.